Trend Micro has discovered a new family of ATM malware called Alice, which is the most stripped down ATM malware family we have ever encountered. Unlike other ATM malware families, Alice cannot be controlled via the numeric pad of ATMs; neither does it have information stealing features. It is meant solely to empty the safe of ATMs. We detect this new malware family as BKDR_ALICE.A.

Trend Micro first discovered the Alice ATM malware family in November 2016 as result of our joint research project on ATM malware with Europol EC3. We collected a list of hashes and the files corresponding to those hashes were then retrieved from VirusTotal for further analysis. One of those binaries was initially thought to be a new variant of the Padpin ATM malware family. However, after reverse analysis, we found that it to be part of a brand new family, which we called Alice.

ATM malware has been around since 2007, but over the past nine years we have only learned of eight unique ATM malware families, including Alice. This new discovery is remarkable because it shows a clear tendency for malware writers to attack an ever-increasing variety of platforms. This is especially acute against ATMs, due to the high monetary value they represent. This tendency has accelerated enormously over the last 2-3 years, which is when the bulk of those families have been discovered.

Technical Details

The family name “Alice” was derived from the version information embedded in the malicious binary:

Figure 1. File properties of Alice sample

Based on PE compilation times and Virustotal submission dates, Alice has been in the wild since at least October 2014. The Alice samples we found were packed with a commercial, off-the-shelf packer/obfuscator called VMProtect. This software checks if the embedded binary is being run inside a debugger and displays the following error message if it determines that to be the case:

Figure 2. Error message

Before any malicious code runs, Alice checks if it is running within a proper Extensions for Financial Services XFS environment to make sure that it’s actually running on an ATM. It does this by looking for the following registry keys:

- HKLM\SOFTWARE\XFS

- HKLM\SOFTWARE\XFS\TRCERR

If these registry keys do not exist, the malware assumes that the environment is not right and terminates itself. Alice also requires the following DLLs to be installed on the system:

- MSXFS.dll

- XFS_CONF.dll

- XFS_SUPP.dll

Depending on whether its XFS check was successful or not, Alice displays either an authorization window or a generic error message box:

Figures 3 and 4. Post-execution message boxes. On the left is an authorization window, which appears if the XFS check is successful. On the right is an error message, which appears if the check yields a negative result.

When first run, Alice creates an empty 5 MB+ sized file called xfs_supp.sys and an error logfile called TRCERR.LOG, both in the root directory. The first file is filled with zeros and no data is ever written to it. The second file (TRCERR.LOG) is a log file that the malware uses to write any errors that occur during execution. All XFS API calls and their corresponding messages/errors are logged. This file is not deleted from the machine during uninstallation. It remains on the system for future troubleshooting, or perhaps the malware author forgot to clean it up.

Alice connects to the CurrencyDispenser1 peripheral, which is the default name for the dispenser device in the XFS environment. Alice does not attempt to connect to other ATM-specific hardware; therefore criminals cannot issue any commands via the PIN pad. Alice doesn’t terminate itself if it fails to connect to CurrencyDispenser1, instead it simply logs the error.

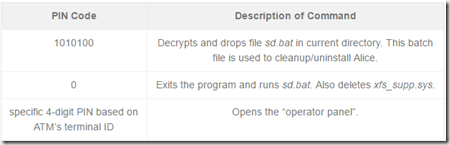

The PIN input seen in Figure 4 provides a way to issue commands to the Alice malware. Three commands can be entered are:

Multiple mistakes in entering the correct PIN will result in the following window being shown and the malware terminating itself:

Figure 5. Error message

When the correct PIN code is entered, Alice will open the “operator panel”. This is a screen showing the various cassettes with money loaded inside the machine, which the attacker can then steal at their leisure. (In this sample, no cassettes are shown since we were running this malware on a test setup.)

Figure 6. Operator panel

Note that entering “0” or “9” as the cassette ID will also cause sd.bat to be run and xfs_supp.sys to be deleted.

When the money mule inputs the cassette number in the operator panel, the CurrencyDispenser1 peripheral is sent the dispense command via the WFSExecute API and stored cash is dispensed. ATMs typically have a 40-banknote dispensing limit, so the money mule might need to repeat the operation multiple times to dispense all the stored cash in the cassette. The stored cash levels for each cassette are dynamically updated on the screen, so the money mule knows how close they are to completely emptying the cassettes.

Alice is usually found on infected systems as taskmgr.exe. While the malware itself has no persistence method, we believe that the criminals manually replace the Windows Task Manager with Alice. Any command that would invoke the Task Manager would instead invoke Alice.

Conclusions

Several things stand out about Alice. It is extremely feature-lean and, unlike other ATM malware families we have dissected, it only includes the basic functionality required to successfully empty the money safe of the ATM. It only connects to the CurrencyDispenser1 peripheral and it never attempts to use the machine’s PIN pad. The logical conclusion is that the criminals behind Alice need to physically open the ATM and infect the machine via USB or CD-ROM, then connect a keyboard to the machine’s mainboard and operate the malware through it.

Another possibility would be to open a remote desktop and control the menu via the network, similar to the hacking attacks in Thailand and other recent incidents. However, we have not seen Alice being used this way. The existence of a PIN code prior to money dispensing suggests that Alice is used only for in-person attacks. Neither does Alice have an elaborate install or uninstall mechanism—it works by merely running the executable in the appropriate environment.

Alice’s user authentication is similar to other ATM malware families. The money mules that carry out the attacks receive from the actual criminal gang(s) the PIN needed. The first command they enter drops the cleanup script, while entering the machine-specific PIN code lets them access the operator panel for money dispensing.

This access code changes between samples to prevent mules from sharing the code and bypassing the criminal gang, to keep track of individual money mules, or both. In our samples the passcode is only 4 digits long, but this can be easily changed. Attempts to brute-force the passcode will eventually cause the malware to terminate itself once the PIN input limit is reached

Given the fact that Alice only looks for an XFS environment and doesn’t perform any additional more hardware-specific checks, we believe that it has been designed to run on any vendor’s hardware configured to use the Microsoft Extended Financial Services middleware (XFS).

One more thing about the use of packers: Alice uses the commercially available VMProtect packer, but it is far from alone. We found GreenDispenser packed with Themida, and Ploutus packed with Phoenix Protector, among others.

Packing makes analysis and reverse engineering more difficult. Common malware has been using this technique for years, with malware today using custom-built packers. So why are ATM malware authors only just now discovering packing and obfuscation techniques?

Up until recently, ATM malware was a niche category in the malware universe, used by a handful of criminal gangs in a highly targeted manner. We are now at a point where ATM malware is becoming mainstream. The different ATM malware families have been thoroughly analyzed and discussed by many security vendors and these criminals have now started to see the need to hide their creations from the security industry to avoid discovery and detection. Today, they are using commercial off-the-shelf packers; tomorrow we expect to see them start to use custom packers and other obfuscation techniques.

Further technical details and a comparison of various ATM malware families can be found in this appendix.

Indicators of Compromise

The files used in this analysis have the following SHA256 hashes:

- 04F25013EB088D5E8A6E55BDB005C464123E6605897BD80AC245CE7CA12A7A70

- B8063F1323A4AE8846163CC6E84A3B8A80463B25B9FF35D70A1C497509D48539

via: trendmicro

Leave a Reply